Music Monday: Mack the Knife

“Mack the Knife” is one of those songs everyone knows because it’s been around for so long, and anyone who’s anyone has sung a version of it–or so it seems. I always thought it was a love song, perhaps a jaded love song (hence “Mack the Knife“). After all, if Sinatra and others sung it, surely it must have some kind of romantic theme?

“Mack the Knife” is one of those songs everyone knows because it’s been around for so long, and anyone who’s anyone has sung a version of it–or so it seems. I always thought it was a love song, perhaps a jaded love song (hence “Mack the Knife“). After all, if Sinatra and others sung it, surely it must have some kind of romantic theme?

I found out a few years ago when I actually read the words and then looked the song up that it’s actually about a serial killer. A fictional serial killer, but a serial killer nevertheless. There’s nothing about love in this song at all, unless it’s old MacHeath’s blood lust. How on earth did a song about a murderer become an American standard? Part of the answer to this is, I think, in some of the clever wording used in the most popular translations. But before I get to that, a bit of history on the song.

Back in the late 1600s, a playwright named John Gay wrote a comic opera called “The Beggar’s Opera” that took a satirical look at government and the upper class by drawing on elements of the criminal world. His main character was a gentleman thief named Macheath who was always polite to his victims and never harmed anyone. A kind of anti-hero type. The opera was very successful and ran for many years.

About 200 years later, just after the First World War, “The Beggar’s Opera” had a revival in London. A guy named Bertolt Brecht got hold of a German translation and in 1927, along with Kurt Weill, reworked the 17th century opera for the early 20th century, both in terms of the characters and the music. They called their version “The Three Penny Opera” (Die Dreigroschenoper), and in it Macheath became “Mackie Messer” (Messer is German for “knife”), a gangster who kills and steals as his “business.” The song “Mack the Knife” was a last minute addition to the show. The tenor who played Mackie thought his character needed a better introduction to the audience, so Brecht and Weill wrote “Mack the Knife” for Police Chief Brown to sing before Mackie comes onstage.

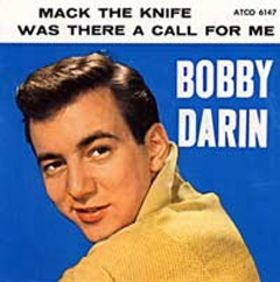

“The Three Penny Opera” was a resounding success, toured extensively, and was translated into multiple languages. The first English translation was in 1933, and there have been at least eight English versions since. Probably the best-known was by Marc Blitzstein, who not only translated the opera, but also cleaned up some of the less savory elements of the original (for example, he removed two verses in “Mack the Knife” about arson and rape). It’s this version of the song that’s been covered by the likes of Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney, Louis Armstrong, Michael Bublé, and, of course, Bobby Darin. It seems Dick Clark had advised Darin against releasing the song since, in his view, the rock-and-roll youngsters wouldn’t appreciate a song from an opera. Darin ignored his advice and released the song. It went to number one on the US Billboard charts for nine weeks in 1959, sold over 2 million copies, and won the Record of the Year Grammy Award in 1960. Frank Sinatra declared Darin’s version of the song to be the definitive version.

With that, let’s take a look at the song. I have to say, I like the way the writer avoids violent words like “blood” or “kill” by using imagery and word-play. For example, the first verse:

Oh the shark, babe, has such teeth, dear, and it shows them pearly white

Just a jackknife has old MacHeath, babe, and he keeps it out of sight.

In other words, the shark is a violent killer and it shows it weapon in full view, and while MacHeath’s as vicious as a shark, he’s more dangerous because he keeps his weapon hidden.

Then verse two:

When that shark bites with his teeth, babe, scarlet billows start to spread

Fancy gloves, though, wears old MacHeath, babe, so there’s never a trace of red

The violent shark leaves a mess of blood when it kills, but MacHeath wears fancy gloves to hide the evidence of his crime. Notice how the writer uses blood colors (scarlet and red) as euphemisms for blood. From the context you know what he’s talking about without him ever having to say the word.

One more, verse three:

Now on the sidewalk, sunny morning, lies a body just oozing life,

And someone’s sneaking around the corner, could that someone be Mack the Knife?

Notice again the clever word substitution: instead of “oozing blood” it’s “oozing life,” which I think is quite evocative. It also gives a neat rhyme for “Mack the Knife.”

Now to the music. I’m using Bobby Darin’s version as the standard English version (if it was good enough for Sinatra, who am I to object?). For years, I knew this song as “the one with all the key changes,” and that is probably one of its most distinctive musical marks. There are five key changes, all chromatic, starting in Bb and ending in Eb. There are seven verses, and the tune and chord progressions are the same for each verse (aside from the key changes). Here’s a lead sheet with the words and guitar chords (click to enlarge):

The “sixth” chords (Bb6, B6, C6, etc.) could be played as straight chords (Bb, B, C, etc.). I included the 6th because it’s in the tune, and it’s possible the guitar on the recording is playing a 6th. How do you play a sixth on the guitar? Like this:

That’s a Bb6. To play a B6, shift this up a fret. A C6? Shift up another fret, and so on. The lines across the strings indicate a barre, so it’s essentially two barres: the longest made with the index finger, the shortest with whatever finger’s most comfortable. I use my pinkie, but I know people who use their ring finger.

Then there are the diminished chords (e.g., Bbº, Bº, Cº, etc.). There are two ways to play those on the guitar. You can use four fingers like this:

Or you can use two fingers and a barre, like this:

That’s a Bbº. Again, for Bº, shift up a fret. Cº, shift up another fret, and so on. I’ve included bass notes, but don’t worry about these on guitar. Indeed, on the recording, after verse two the bass goes walkabout, so for both piano and guitar, do whatever sounds good to you!

Now that last chord. After listening to it carefully a number of times, the best I can come up with is an Eb ninth with the sixth added (which I’ve written Eb9/6). I can definitely hear the dominant seventh note (Db), and the 6th is wailing through on the trumpets (a C). I’m pretty sure the 9th is in there too (an F). How to play this on guitar? This is the best I can come up with:

And on piano, something like this:

Finally, the videos. Here’s Bobby Darin “performing” (i.e., lip-syncing) to the song on Dick Clark’s “Saturday Night Beech-Nut Show” in 1959:

And here’s a clip from The Muppet Show, where Dr. Teeth is trying to convince Sam the Eagle that the words to “Mack the Knife” are really not as bad as they sound:

Any questions, comments, or suggestions for future songs to feature? Comment below or email me!

1 Response

2question